SpaceX shared its plans to send mankind to Mars with the intent to colonize the planet. The company wants to sens its spaceship back and forth in a set frequency to supply that colony. According to Elon Musk the goal of humans is to be an interplanetary species.

The presentation, which was streamed live, lasted about an hour. It was followed by a question-and-answer session, during which space news reporters split microphone time with eccentric fans, self-promoters and even one attendee attempting to solicit a kiss from Musk himself as planetary.org reports:

Musk's plans are so ambitious, they nearly defy analysis. Of all the modern private space firms claiming they will ferry tourists to orbit, mine asteroids and set up commercial space stations, SpaceX may stand alone in its ability to present such a staggeringly audacious plan and still be taken seriously. Even NASA might raise more objections if it were to drop an equally zealous version of its current Journey to Mars plans.

Put simply, Musk wants to colonize Mars. Humanity, he believes, must become an interplanetary species before some future calamity wipes our presence from the Earth.

Whereas NASA's humans-to-Mars plans envision an Antarctica-like research station with a rotating crew of astronauts, Musk wants to have a million people there in 40 to 100 years. He stopped short of saying he wanted to terraform the planet, but frequently alludes to the possibility; SpaceX's new video on its Mars transportation system ends by showing the Red Planet spinning into an Earth-like orb.

The plan

Musk envisions up to 100 Mars-bound colonists boarding an oblong spacecraft perched atop a massive rocket at Kennedy Space Center's launch pad 39A. The rocket's width would be 12 meters; the entire stack would top 122 meters. By comparison, the Saturn V was 111 meters tall and 10 meters wide at the bottom; NASA's Space Launch System will debut at 98 meters tall and 8.4 meters wide.

The rocket would be powered by a staggering 42 engines, generating 28.7 million pounds of thrust at liftoff. That's almost exactly four times more powerful than the Saturn V, which had just five engines. The only other vehicle to attempt an engine configuration on this scale was the Soviet N-1 moon rocket, which had 30 engines and was destroyed four times in four launch attempts.

The booster rocket blasts the Mars colonists into a parking orbit before returning directly to its launch pad for an upright landing. Next, a pad crane lifts a nearby propellant tanker—shaped similarly to the colonists' spaceship—onto the reused booster. The rocket launches again, sending the tanker into orbit to rendezvous with the passenger ship. After a fuel transfer, it's on to Mars for the colonists, while the booster and tanker return to Florida to repeat the process.

Musk's diagrams showed an intention to reuse the booster 1,000 times and the fuel tanker 100 times. That sort of reusability is utterly without precedent; the most re-flown spacecraft of all time is space shuttle Discovery, which completed 39 missions in 27 years. Discovery and its sibling shuttles could carry a crew of seven into low-Earth orbit for a couple weeks; the Mars colonial spaceship would spend between 90 and 150 days en route to Mars.

The cost

Musk estimated it would take $10 billion to develop his transport system. That's optimistic, but in the realm of possibilities. In 1972, NASA estimated space shuttle development would cost $5.15 billion—roughly $30 billion in today's dollars (not counting cost overruns).

SpaceX's estimated cost to build a single booster, tanker and transport ship is $560 million dollars. After the Challenger disaster, NASA paid $1.7 billion for space shuttle Endeavour. By the time the shuttles retired in 2011, it was estimated the program had cost of $209 billion.

Whatever the price tag, it remains to be seen exactly how SpaceX would pay for all this. During the presentation, Musk jokingly used a South Park reference (underpants gnomes) before saying the company would continue focusing on its core business of launching satellites and sending NASA crew and cargo missions to the International Space Station.

At the moment, it can do neither. Earlier this month, a Falcon 9 rocket exploded during a routine propellant filling operation, marking the company's second payload loss in 15 months. SpaceX has yet to find the cause of the accident, though they recently said the problem appeared to have originated in the rocket's upper stage helium pressurization system (notably, Musk said the company's new rocket booster would be autogeneously pressurized and not require such a design).

Ramping up

Right now, Musk estimates less than 5 percent of his company is working on the Mars project. What few employees are appear to be working overtime; Musk used the phrase "seven days a week" days to describe recent efforts to complete a carbon fiber liquid oxygen tank and test-fire the company's new Raptor engine.

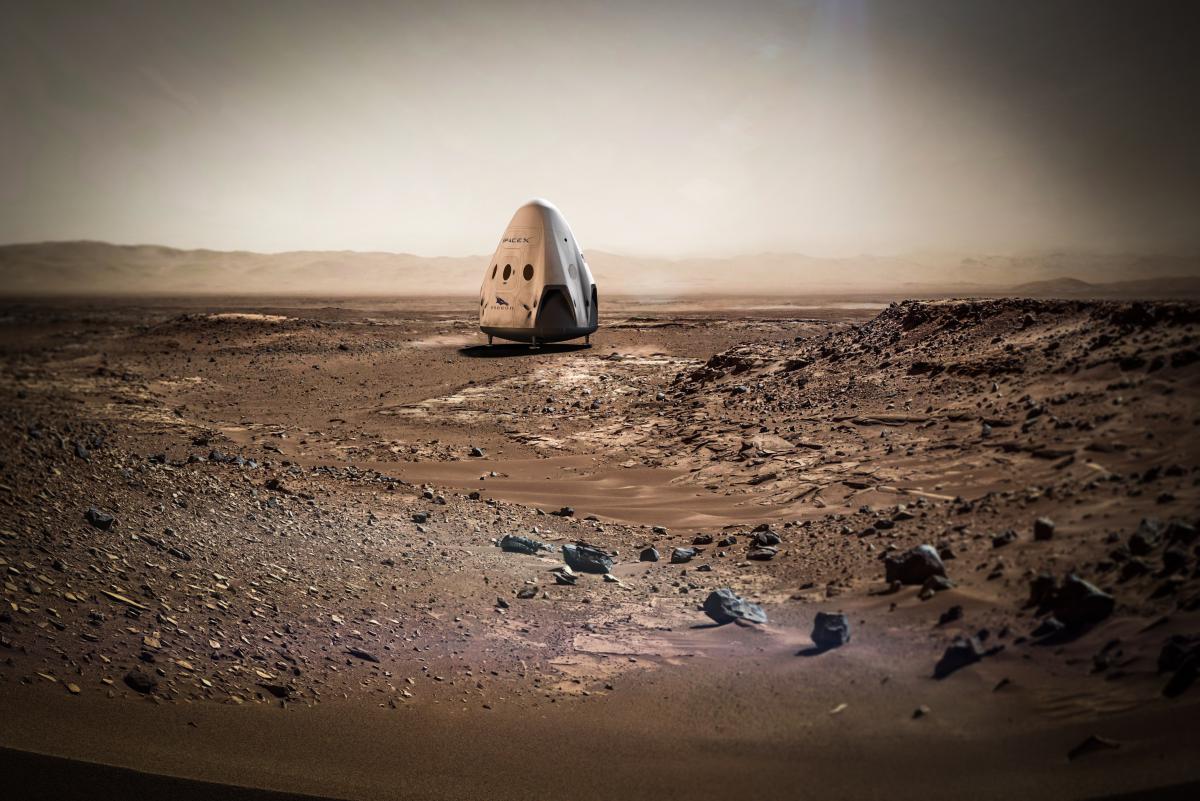

That 5 percent figure will likely need to increase—soon. While conceding he doesn't always stick to promised timelines, Musk offered a diagram that showed booster tests starting in 2019, orbital flights kicking off in 2020, and trips to Mars beginning in late 2022. In the meantime, the first Red Dragon—a Mars-capable version of the company's upcoming Crew Dragon capsule—is still scheduled to fly in 2018. Musk also said the Falcon Heavy rocket, which is essentially three Falcon 9 vehicles strapped together, would debut early next year.

Despite all the details revealed in today's presentation, many questions remain: What kind of life support systems will be used? Where will SpaceX build all this? How will the colonists stay healthy on their trip? And on Mars? What kind of infrastructure will support them there? Will SpaceX build a NASA-esque Deep Space Network for Mars communications? The list goes on and on.

There are also ethical considerations. NASA builds its spacecraft with the mentality that "failure is not an option," always keeping in mind tragedies like Columbia, Challenger and Apollo 1. Musk, on the other hand, openly admits people are likely to die.

And what about planetary protection? Will SpaceX's vision of the future clash with detractors that wish to keep the planet pristine?

Since the moon landings, we have largely trusted NASA to decide how, when—and to some degree, why—humanity should make its first giant leap to another world. Despite the very real questions about whether America's space agency can sustain the political and programmatic momentum needed to land humans on Mars in the mid-2030s, they stand alone atop the list of possible contenders.

Until perhaps now.

Elon Musk's claim that he can develop a million-person-strong colony on Mars in 40 to 100 years deserves scrutiny. But there's no doubt he's going to try, and we're likely to see a lot of fantastic innovations along the way.

Musk's plans are also likely to spark the imaginations of the next generation of scientists and engineers that will pick up the baton, should SpaceX fall short. In what can sometimes feel like a world full of impossibilities, SpaceX is trying to reset the idea of what is possible.