Pascal GPU Architecture

The Pascal GP107 GPU

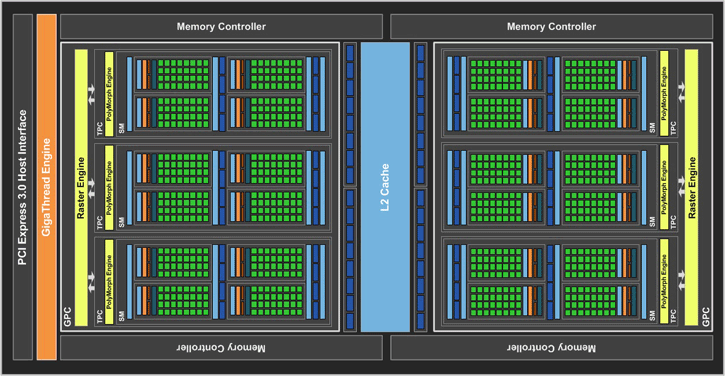

The GPU is based on a DX12 compatible architecture called Pascal. Much like in the past designs you will see pre-modeled SMX clusters that hold what is 2x64 shader processors per cluster. Pascal GPUs are composed of different configurations of Graphics Processing Clusters (GPCs), Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs), and memory controllers. Each SM is paired with a PolyMorph Engine that handles vertex fetch, tessellation, viewport transformation, vertex attribute setup, and perspective correction. The GP107 PolyMorph Engine also includes new Simultaneous Multi-Projection units. There are 6 active (SM) clusters for a fully enabled Pascal GP107 GPU. The GeForce GTX 1050 Ti is fully enabled, the non-Ti model 1050 thus has one cut out thus holding 5 SM clusters.

- The GeForce GTX 1050 (GP107-300) has 5 x 128 shader processors which make a total of 640 shader processors.

- The GeForce GTX 1050Ti (GP107-400) has 6 x 128 shader processors which make a total of 768 shader processors.

- The GeForce GTX 1060 (3GB) (GP104-400) has 9 x 128 shader processors which make a total of 1,152 shader processors.

- The GeForce GTX 1060 (6GB) (GP104-400) has 10 x 128 shader processors which make a total of 1,280 shader processors.

- The GeForce GTX 1070 (GP104-200) has 15 x 128 shader processors which make a total of 1,920 shader processors.

- The GeForce GTX 1080 (GP104-400) has 20 x 128 shader processors which make a total of 2,560 shader processors.

Each SM, however, has a cluster of 64 shader / stream / cuda processors doubled up. Don't let that confuse you, it is 128 shader units per SM. Each GPC ships with a dedicated raster engine and five SMs. Each SM contains 128 CUDA cores, 256 KB of register file capacity, a 96 KB shared memory unit, 48 KB of total L1 cache storage, and eight texture units.

As far as the memory specs of the GP107 GPU are concerned, these boards will feature a 128-bit memory bus connected to 2 or 4 GB of GDDR5 video memory, AKA VRAM AKA framebuffer AKA graphics memory for the graphics card. The GeForce GTX 1000 series are DirectX 12 ready, in our testing, we'll address some Async compute tests as well. The latest revision of DX12 is a Windows 10 feature only but can bring in significant optimizations. For your reference, below is a quick overview of some past generation high-end GeForce cards. With 4 GB graphics memory available for one GPU, the GTX 1050 Ti is very attractive for entry level modern and future games no matter what resolution you game at. 1080P and 4 GB are fine.

Pascal Graphics Architecture

Let's place the more important data on the GPU into a chart to get an idea and better overview of changes in terms of architecture like shaders, ROPs and where we are at frequencies wise:

So we talked about the core clocks, specifications, and memory partitions. However, to be able to better understand a graphics processor you simply need to break it down into tiny pieces. Let's first look at the raw data that most of you can understand and grasp. This bit will be about the architecture. NVIDIA’s “Pascal” GPU architecture implements a number of architectural enhancements designed to extract even more performance and more power efficiency per watt consumed. Above, in the chart photo, we see the block diagram that visualizes the architecture, Nvidia started developing the Pascal architecture around 2013/2014 already. The GPCs has 6 SMX/SMM (streaming multi-processors) clusters in total. You'll spot six 32-bit memory interfaces, bringing in a 128-bit path to the graphics GDDR5 or GDDR5X memory. Tied to each 32-bit memory controller are eight ROP units and 256 KB of L2 cache. The full GP107 chip used in the GTX 1050 Ti thus has a total of 32 ROPs and 1,024 KB of L2 cache.

A fully enabled GP104 GPU will have (GTX 1080):

- 2,560 CUDA/Shader/Stream processors

- There are 128 CUDA cores (shader processors) per cluster (SM)

- 7.1 Billion Transistors (FinFet at 16 nm)

- 160 Texture units

- 64 ROP units

- 2 MB L2 cache

- 256-bit GDDR5X

A partially disabled GP104 GPU will have (GTX 1070):

- 1,920 CUDA/Shader/Stream processors

- There are 128 CUDA cores (shader processors) per cluster (SM)

- 7.1 Billion Transistors (FinFet at 16 nm)

- 120 Texture units

- 64 ROP units

- 2 MB L2 cache

- 256-bit GDDR5

A fully enabled GP106 GPU will have (GTX 1060):

- 1,280 CUDA/Shader/Stream processors

- There are 128 CUDA cores (shader processors) per cluster (SM)

- 4 Billion Transistors (FinFet at 16 nm)

- 80 Texture units

- 48 ROP units

- 2 MB L2 cache

- 192-bit GDDR5

A fully enabled GP107 GPU will have (GTX 1050 Ti):

- 768 CUDA/Shader/Stream processors

- There are 128 CUDA cores (shader processors) per cluster (SM)

- 3.3 Billion Transistors (FinFet at 16 nm)

- 48 Texture units

- 32 ROP units

- 1 MB L2 cache

- 192-bit GDDR5

- GeForce GTX 960 has 8 SMX x 8 Texture units = 64

- GeForce GTX 970 has 13 SMX x 8 Texture units = 104

- GeForce GTX 980 has 16 SMX x 8 Texture units = 128

- GeForce GTX Titan X has 24 SMX x 8 Texture units = 192

- GeForce GTX 1050 (2GB) has 5 SMX x 8 Texture units = 40

- GeForce GTX 1050 Ti (4GB) has 6 SMX x 8 Texture units = 48

- GeForce GTX 1060 (3GB) has 9 SMX x 8 Texture units = 72

- GeForce GTX 1060 (6GB) has 10 SMX x 8 Texture units = 80

- GeForce GTX 1070 has 15 SMX x 8 Texture units = 120

- GeForce GTX 1080 has 20 SMX x 8 Texture units = 160

So there's a total of 6 SMX x 8 TU = 48 texture filtering units available (Ti).

Asynchronous Compute

Modern gaming workloads are increasingly complex, with multiple independent, or “asynchronous,” workloads that ultimately work together to contribute to the final rendered image. Some examples of asynchronous compute workloads include:

- GPU-based physics and audio processing

- Postprocessing of rendered frames

- Asynchronous timewarp, a technique used in VR to regenerate a final frame based on head position just before display scanout, interrupting the rendering of the next frame to do so

These asynchronous workloads create two new scenarios for the GPU architecture to consider. The first scenario involves overlapping workloads. Certain types of workloads do not fill the GPU completely by themselves. In these cases there is a performance opportunity to run two workloads at the same time, sharing the GPU and running more efficiently — for example, a PhysX workload running concurrently with graphics rendering. For overlapping workloads, Pascal introduces support for “dynamic load balancing.” In Maxwell generation GPUs, overlapping workloads were implemented with static partitioning of the GPU into a subset that runs graphics, and a subset that runs compute. This is efficient provided that the balance of work between the two loads roughly matches the partitioning ratio. However, if the compute workload takes longer than the graphics workload, and both need to complete before new work can be done, and the portion of the GPU configured to run graphics will go idle. This can cause reduced performance that may exceed any performance benefit that would have been provided from running the workloads overlapped. Hardware dynamic load balancing addresses this issue by allowing either workload to fill the rest of the machine if idle resources are available. Time-critical workloads are the second important asynchronous compute scenario. For example, an asynchronous timewarp operation must complete before scanout starts or a frame will be dropped. In this scenario, the GPU needs to support very fast and low latency preemption to move the less critical workload off of the GPU so that the more critical workload can run as soon as possible. As a single rendering command from a game engine can potentially contain hundreds of draw calls, with each draw call containing hundreds of triangles, and each triangle containing hundreds of pixels that have to be shaded and rendered. A traditional GPU implementation that implements preemption at a high level in the graphics pipeline would have to complete all of this work before switching tasks, resulting in a potentially very long delay. To address this issue, Pascal is the first GPU architecture to implement Pixel Level Preemption. The graphics units of Pascal have been enhanced to keep track of their intermediate progress on rendering work, so that when preemption is requested, they can stop where they are, save off context information about where to start up again later, and preempt quickly. In the command pushbuffer, three draw calls have been executed, one is in process and two are waiting. The current draw call has six triangles, three have been processed, one is being rasterized and two are waiting. The triangle being rasterized is about halfway through. When a preemption request is received, the rasterizer, triangle shading and command pushbuffer processor will all stop and save off their current position. Pixels that have already been rasterized will finish pixel shading and then the GPU is ready to take on the new high priority workload. The entire process of switching to a new workload can complete in less than 100 microseconds (μs) after the pixel shading work is finished. Pascal also has enhanced preemption support for compute workloads. Thread Level Preemption for compute operates similarly to Pixel Level Preemption for graphics. Compute workloads are composed of multiple grids of thread blocks, each grid containing many threads. When a preemption request is received, the threads that are currently running on the SMs are completed. Other units save their current position to be ready to pick up where they left off later, and then the GPU is ready to switch tasks. The entire process of switching tasks can complete in less than 100 μs after the currently running threads finish. For gaming workloads, the combination of pixel level graphics preemption and thread level compute preemption gives Pascal the ability to switch workloads extremely quickly with minimal preemption overhead.